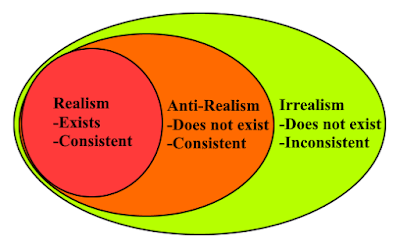

Does the universe exist? Is math real? Which Star Wars timeline is the true Star Wars? These questions fall under the philosophical field of ontology, the contemplation of what exists and how. In this post, we will look at what I consider to be the three main ontological categories that concepts can fall into: Realism, Anti-Realism, and Irrealism.

Realism

We have talked extensively about Realism on this blog, so today let’s take a look at the basics of the theory in its most abstract form. Anything that is real has a property called existence, which means it has way-that-it-is, independent of perception, knowledge, and belief. Real things are not contained by boundaries of reductionism and holism, which means it is equally valid to consider all of Reality at once, or to divide it into an infinite number of infinitesimal pieces.

Reality can be relative, but it is consistent. This means things can “look” different from different “perspectives,” but they “look” the same from the same “perspective” at any one moment in time. I use quotes here, because it doesn’t actually require anyone to be there to observe it.

A thing that is real exists, and it is consistent with itself and in its relation to all other parts of Reality.

Anti-Realism

This will come as no surprise to anyone, but not all things are real. However, it turns out that some unreal things are very useful for describing reality, in particular conceptual frameworks that are non-contradictory within themselves. A mental construct that does not exist, but is self-consistent is called anti-real.

The prime example of something anti-real is math. People argue sometimes whether math is real or not, but I think they would be delighted to find out that there is another ontological category it fits into. Math does not exist in objective reality, but it behaves like something real; it is consistent with itself.

Math is a lot more than numbers. It also includes vectors, functions, groups, sets, and all kinds of things. What ties all of math together is its process: we begin by defining a number of axioms, and determine as much as we can that follows logically from those axioms. This, by definition, is consistent. If there is ever a contradiction in a mathematical construct, the offending object is deemed invalid, or the axioms need to be reevaluated. There is no number in the real numbers that is both smaller than one and larger than two.

Logic is anti-real. Some would say scientific paradigms are anti-real, though it would be more accurate to say science uses anti-real models to describe real things.

A thing that is anti-real does not exist, but it is consistent with itself and in its relation to all other things within its conceptual framework.

Irrealism

Things that exist and are consistent are real. Things that are consistent but do not exist are anti-real. And we have one more realm to examine: that which is irreal neither exists nor is consistent.

Essentially, Irrealism is a tool of interpretations and descriptions. It says that, if two or more descriptions have gaps, but they account for each other’s gaps, then even if the descriptions contradict each other, they form a valid composite description when taken together.

If you’re like me, you find Irrealism highly confusing. The best way I know of to get a feel for it is by looking at a bunch of examples.

The most intuitive example of Irrealism I can think of is fiction. When you and I read a book, the version of the story in your imagination is very different from the one in my imagination. These two versions contradict each other in many ways. Yet they still count as valid interpretations of the same story. Thus, fiction is irreal.

A clear view of a story’s irreality can be found in retconning, when a book or a movie later in a series contradicts something that happened early in the series. Arguably, the events of a first book ripple into the fourth book, so when the fourth book declares that something that happened in the first book is wrong, we have a scenario that requires both that the first book is right and that the first book is wrong. In the worst case scenarios, both sides of the contradiction must be true in order for the fourth book to make sense! Thus, the established canon of the fourth book is irreal.

It has been quite hard for me to think of examples of irrealism that the average person will understand. After ret-conning, all I could come up with involve frontier physics and philosophy, so that’s what the rest of this section will be about. So, warning, heady topics ahead.

Irrealism was originally proposed as a theory to reconcile the two major metaphysical theories, Physicalism and Phenomenalism. Physicalism says that the true reality is physical reality, and Phenomenalism says that the true reality is that which is experienced by conscious observers.

The difference between physicalism and phenomenalism can be illustrated by the question, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound?” According to Physicalism, it does. The sound wave is there in the air whether or not anyone is there to hear it. But according to Phenomenalism, if no one hears it, there is no sound, because things only exist if they are experienced.

Phenomenalism has trouble explaining why things are consistent between times when they are being observed. Physicalism explains that, but has trouble explaining consciousness. Metaphysical Irrealism says that’s okay. Despite the fact that they contradict one another, they cover each other’s gaps, and therefore the composite Physicalism+Phenomenalism is a valid representation of the truth, and there is no single non-contradictory theory that accounts for all of reality.

What about quantum physics? Most claims about reality citing quantum physics are bogus, but there is one sense in which Irrealism might be applicable. There are two major interpretations of quantum physics: the Copenhagen interpretation and the Many-Worlds interpretation. Copenhagen explains probabilities, but not the collapse of the wave function. Many-Worlds explains the collapse of the wave function, but not probabilities. A quantum irrealist would say that even though they contradict one another, all questions are explained between them, so the truest representation of quantum physics is the composite Copenhagen+Many-Worlds.

And one more physics example. General Relativity explains how things behave in extremely high gravity, and Quantum Mechanics explains how things behave at the very small scales. However, they do not play nice together. If we try thought experiments with both extremely high gravity and very small scales, we get contradictions between the theories. A physical irrealist would say, if we never have to deal with things in the quantum gravity regime, then it’s perfectly reasonable to say the composite theory GR+QM is the truest description there is.

Why It Matters

You may have your own opinion on where Realism, Anti-Realism, and Irrealism apply. But you may also be wondering, “what does it matter?” The common answer to this is that, if we understand how things really are, we can use that knowledge to more effectively achieve the outcomes we want. As evidence, we can point to technology; knowing how the world works lets us take materials and put them together to make tools that work for our purposes.

But that’s not an argument for metaphysics, it’s an argument for pragmatism. The point of pragmatism is to focus on what is useful, not what is true. And according to a research team led by the psychologist Donald Hoffman, usefulness and truth are rarely the same thing.

|

| The results of a study of evolutionary simulations, summarized in a Ted Talk. |

Personally, I am motivated to search for true descriptions because I have a passion and a talent for it, and doing so fills me with energy and excitement. However, I have no illusion that this makes me superior in any way to people who don’t have the interest or skills to contemplate metaphysical theories. It just happens to be one of the ways I pursue fulfillment, and other people have their own paths to fulfillment.

However, there is one domain where Realism is both true and deeply important: suffering. Suffering is something experienced directly by conscious beings, and it is most definitely real. When people and animals suffer, turning our gaze away does not make the suffering stop being real. It is an objective fact that subjective suffering exists where it exists. Thus, it is extremely important to recognize the suffering of others as real, and to do what we can to alleviate that suffering and help each other on the path toward relief, meaning, and fulfillment.

No comments:

Post a Comment