With the dawn of science, we learned that the stars are other suns, each with its own set of planets. Stars come in many sizes and colors, depending on what they are made of and how far along they are in their life cycle. A star’s light comes from its surface temperature, as it radiates its heat energy away. The hotter the star, the brighter it shines, and the higher the peak frequency of its light. It is the same as why metals glow when they are heated. In order of increasing temperature, we get red, orange, yellow, white, and then blue. Because of the distribution of the light radiated, and the way our eyes work, we will never find a green or purple star.

A star forms when the gas (mostly hydrogen) in a region of space becomes dense enough that its gravity causes it to collapse together. As it shrinks, the tiny bits of angular momentum here and there build up, causing it to swirl around and form a protoplanetary disk. Most of the gas clumps in the center, forming the star, and the rest eventually becomes planets, moons, and asteroids. While this is happening, the star is called a protostar.

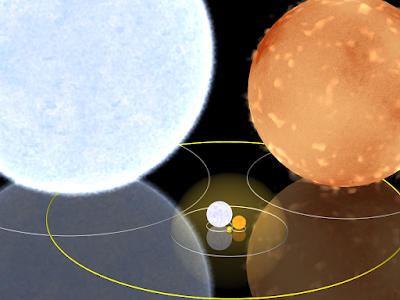

Once all of the dust has settled, the star officially begins its life, and is called a main sequence star. The mass of the star determines how hot it is, and therefore its color. From low to high, we have red dwarfs, orange dwarfs, yellow dwarfs, and blue . . . giants. A star massive enough to shine blue at birth is too big to be called a dwarf.

Our sun is a yellow dwarf, although it’s actually white, not yellow. The reason it looks yellow, orange, or red when it is low in the sky is because Earth’s atmosphere scatters the shorter wavelengths. this is also why the daytime sky is blue.

There are also brown dwarfs, but they are a little different. Brown dwarfs are objects that ride the fuzzy line between stars and gas giant planets, only hot enough to glow a faint dark red. They are a little over ten times the mass of Jupiter, and a hudredth the mass of the sun.

Stars don’t stay as they are forever. As they fuse up their hydrogen, they expand. A lot. As in, orders of magnitude. Once their hydrogen is spent, they contract until the helium in their cores begins to fuse. As the helium runs low, they expand again. The cycle goes on a few more times. When stars are in their expansion phase, they are called giants, supergiants, or hypergiants depending on their masses, and their color shifts toward the red end of the spectrum. Some stars, however, are so blue that they remain blue even at their largest.

These are all the types of stars that we know about that are around today. However, despite the nearly 14 billion years the universe has been around, it is very young compared to how old it will get. The smaller a star, the slower it fuses its fuel, so the longer every stage of its life lasts. In fact, red dwarf stars are so slow that none of them have used up all of their hydrogen yet. Here’s where things get interesting. It is predicted that red dwarfs don’t expand like other stars. Instead, they get hotter and brighter, turning into blue dwarfs. I find it just amazing that some trillion years in the future, a star type the universe has never seen before will start to appear.

But wait, you say. We can’t be done with stars yet! We haven’t talked about white dwarf stars or neutron stars. And you are correct. The reason we haven’t talked about them today is because they are dead stars, and dead stars are interesting enough that I wanted to give them their own discussion.

No comments:

Post a Comment